The European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) represents the world’s first comprehensive regulation of artificial intelligence systems. Understanding who qualifies as a “provider” under this regulation is crucial for compliance, as providers bear the most significant responsibilities and potential liabilities under the Act. In this guide, we provide an exhaustive analysis of the “AI provider” definition based on the official text of the AI Act.

Official Definition of “Provider”

According to Article 3(3) of the EU AI Act, the official definition states:

‘Provider’ means a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body that develops an AI system or a general-purpose AI model or that has an AI system or a general-purpose AI model developed and places it on the market or puts the AI system into service under its own name or trademark, whether for payment or free of charge;

This definition establishes several key criteria that determine provider status under the AI Act.

Breaking Down the Provider Definition: Who Can Be a Provider?

The Act defines providers broadly to encompass various types of entities. Natural persons, which include individuals operating in their professional capacity, can qualify as providers if they meet the definitional criteria.

Legal persons such as companies and corporations represent the most common category of providers, spanning from startups developing AI applications to multinational technology companies creating sophisticated AI systems.

Public authorities and government agencies also fall within the provider definition when they develop AI systems for public services or administrative functions. This inclusion ensures that government-deployed AI systems, such as those used in public administration, law enforcement support systems, or citizen services, are subject to the same regulatory framework as private sector AI development.

The definition’s inclusion of “other bodies” creates a catch-all category that captures any organizational entity involved in AI development or deployment that might not fit neatly into the other categories.

This broad approach reflects the EU’s intention to create a comprehensive regulatory framework that adapts to the diverse organisational structures involved in AI development.

Core Activities That Define a Provider Under AI Act

Provider status fundamentally depends on two primary activities: direct development of AI systems or general-purpose AI models, and commissioning such development from third parties.

Direct development encompasses the traditional understanding of AI creation, where an entity designs, builds, and creates AI systems using their own resources, expertise, and infrastructure.

Beyond Traditional Development: Expanding the Provider Definition

However, the definition’s inclusion of entities that “have an AI system or a general-purpose AI model developed” significantly expands the scope beyond traditional developers. This means that companies who outsource AI development while maintaining control over the process and ultimate responsibility for the system also qualify as providers. This approach recognizes that modern AI development often involves complex partnerships, outsourcing arrangements, and collaborative development models.

The key distinction lies in control and responsibility rather than direct technical involvement. An entity that commissions AI development, provides specifications, maintains oversight of the development process, and takes responsibility for the final product qualifies as a provider even if they never write a line of code themselves.

What Market Activities Can Providers Exercise to Fall Under AI Act?

Beyond development, provider status requires engagement in specific market activities. Placing an AI system on the market, as defined in Article 3(9), involves “the first making available of an AI system or a general-purpose AI model on the Union market.” This encompasses the initial commercial release, distribution, or availability of an AI system within the EU economic area.

Putting an AI system into service, defined in Article 3(11) as “the supply of an AI system for first use directly to the deployer or for own use in the Union for its intended purpose,” covers deployment scenarios where systems are directly supplied to end users or deployed for the provider’s own operational use. This distinction is important because it captures both commercial distribution and internal deployment scenarios.

The market activity requirement ensures that the provider definition captures entities that have moved beyond research and development into actual deployment or commercialization of AI systems. This threshold helps distinguish between experimental or prototype development and systems that have entered operational use where regulatory oversight becomes critical.

Should Providers Trade Under Own Name or Trademark?

The requirement that AI systems be offered under the provider’s own name or trademark establishes a responsibility and accountability link. This means the entity must be publicly associated with the AI system and take commercial and legal responsibility for its performance and compliance.

This requirement prevents entities from avoiding provider obligations by acting as anonymous developers or hidden controllers of AI systems.

The trademark or name requirement also helps establish clear chains of responsibility in complex AI supply chains.

When an AI system bears a specific company’s name or trademark, that company becomes the accountable provider regardless of the underlying development arrangements or partnerships that may have contributed to the system’s creation.

Commercial Considerations for Defining AI Providers Under AI Act

One of the most significant aspects of the provider definition is its explicit statement that provider status applies “whether for payment or free of charge.” This provision has far-reaching implications for the AI ecosystem, particularly for open-source AI development, academic research distribution, and companies that offer AI services without direct monetary charges.

The inclusion of free-of-charge distribution means that companies offering AI systems supported by advertising revenue, data collection, or other indirect monetization models cannot escape provider obligations simply because users don’t pay directly for the AI system.

Similarly, open-source AI developers who make their systems freely available still bear provider responsibilities if they meet the other definitional criteria.

This approach reflects the EU’s recognition that AI systems can create significant societal impacts regardless of their business model. The potential for harm, bias, or misuse exists whether the AI system is sold for profit, offered as a free service, or distributed as open-source software.

Related Definitions That Impact Provider Status in AI Act

Who is a Downstream Provider?

Article 3(68) introduces the concept of a downstream provider: “a provider of an AI system, including a general-purpose AI system, which integrates an AI model, regardless of whether the AI model is provided by themselves and vertically integrated or provided by another entity based on contractual relations.”

This definition recognizes the increasingly common practice of building AI systems by integrating existing AI models, whether developed internally or obtained from third parties. Companies that create AI applications by incorporating pre-trained models, foundation models, or AI services from other providers become downstream providers with their own set of obligations under the Act.

What is a General-Purpose AI Model?

The definition of general-purpose AI models in Article 3(63) significantly impacts provider obligations. These models are characterized by their “significant generality” and capability to “competently perform a wide range of distinct tasks regardless of the way the model is placed on the market.”

The definition specifically excludes models “used for research, development or prototyping activities before they are placed on the market.”

This distinction is crucial because general-purpose AI models, particularly those with high-impact capabilities, face additional regulatory requirements under the Act. Providers of such models must meet enhanced obligations related to risk assessment, documentation, and systemic risk management.

And Finally, What is an AI System?

The broad definition of AI systems in Article 3(1) as “machine-based systems designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy” that can “generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions” ensures that the provider definition captures a wide range of technologies beyond traditional narrow AI applications.

Practical Scenarios: Who Is and Isn’t a Provider?

Understanding provider status requires examining real-world scenarios. A software company that develops and sells AI-powered chatbots clearly qualifies as a provider, as they develop the system and place it on the market under their own brand.

Similarly, a tech startup creating facial recognition systems and licensing them to retailers meets all provider criteria through development and market placement activities.

Healthcare companies developing AI diagnostic tools represent another clear provider scenario. Whether they deploy these tools in their own facilities or license them to other healthcare providers, they qualify as providers through their development activities and system deployment under their own brand.

Government agencies that develop AI systems for public services also fall within the provider definition. This includes agencies creating AI systems for benefit administration, public safety applications, or citizen service chatbots. The public sector nature of these entities doesn’t exempt them from provider obligations when they develop and deploy AI systems.

Downstream providers present more complex scenarios. An e-commerce platform that integrates third-party recommendation AI models into their system becomes a downstream provider, even though they didn’t develop the underlying AI model. Their integration work creates a new AI system that they place on the market under their own brand, triggering provider obligations.

Mobile app developers who incorporate pre-trained language models into their applications similarly become downstream providers. The integration of existing AI models into new applications or services creates provider responsibilities, regardless of who developed the underlying models.

Automotive manufacturers present particularly interesting cases as downstream providers. When they integrate AI driving assistance models into their vehicles, they become providers of the integrated AI system, even if the underlying AI models were developed by specialised AI companies. The manufacturer’s integration work, combined with marketing the vehicles under their own brand, establishes provider status.

Key Distinctions from Other Roles

The provider role must be distinguished from other roles defined in the AI Act. Deployers, as defined in Article 3(4), are entities “using an AI system under its authority except where the AI system is used in the course of a personal non-professional activity.”

The fundamental difference lies in the relationship to the AI system: providers develop, commission, or place AI systems on the market, while deployers use AI systems for their intended purposes. We will discuss this in a separate article.

This distinction isn’t always clear-cut, as the same entity can serve as both provider and deployer for different AI systems. A company might be a provider for AI systems they develop and market, while simultaneously being a deployer for AI systems they purchase and use from other providers for their internal operations.

The concept of “operator” serves as an umbrella term that includes providers along with product manufacturers, deployers, authorised representatives, importers, and distributors.

Understanding this hierarchy helps clarify that provider is a specific type of operator with distinct obligations, rather than a separate category outside the operator framework.

Provider Obligations Under the AI Act

Provider status carries the most extensive obligations under the AI Act, particularly for high-risk AI systems. These obligations reflect the EU’s approach of placing primary responsibility on entities that have the greatest control over AI system development and deployment.

For high-risk AI systems, providers must implement comprehensive risk management systems that identify, analyse, and mitigate risks throughout the AI system lifecycle.

Data governance requirements ensure that training, validation, and testing data meet quality standards and avoid bias that could lead to discriminatory outcomes.

Technical documentation obligations require providers to maintain detailed records of their AI systems’ design, development, and performance characteristics. This documentation must be sufficiently comprehensive to enable regulatory authorities and users to understand the system’s capabilities, limitations, and appropriate use cases.

Transparency and information provision requirements mandate that providers give users clear information about AI system capabilities, limitations, and proper usage. This includes providing instructions for use that enable deployers to use the AI system safely and in accordance with its intended purpose.

Quality management systems represent another significant obligation, requiring providers to establish organisational processes that ensure consistent compliance with AI Act requirements throughout their operations. These systems must address everything from development practices to post-market monitoring and incident response.

International and Cross-Border Considerations

The AI Act’s territorial scope extends beyond EU-based providers to encompass international entities whose AI systems affect the EU market. Non-EU providers fall within the Act’s scope when:

- Their AI systems are placed on the EU market

- Put into service within the EU

- The output produced by their systems is used in the EU.

This extraterritorial application means that companies based in countries like the United States, China, or anywhere else in the world must comply with AI Act requirements if their AI systems have EU market presence or impact.

The regulation follows the “Brussels Effect” model, where EU regulations influence global business practices due to the size and importance of the EU market.

Non-EU providers may need to appoint authorised representatives within the EU to fulfill their obligations under the Act. Article 3(5) defines authorised representatives as EU-based entities that accept written mandates to perform AI Act obligations on behalf of non-EU providers.

This mechanism ensures that EU authorities have accessible points of contact and accountability for all AI systems affecting the EU market.

Compliance Implications for AI Providers

Determining provider status has significant implications for compliance obligations and associated costs.

First of all, organisations must carefully assess their AI-related activities to understand whether they qualify as providers and, if so, which specific obligations apply to their AI systems.

The assessment process should examine development involvement, including both direct development activities and arrangements where development is commissioned from third parties.

Market activities must also be analysed to determine whether the organisation places AI systems on the market or puts them into service. The analysis should also consider control and responsibility factors, particularly whether AI systems are offered under the organisation’s name or trademark.

Geographic scope presents another critical consideration, as organizations must evaluate whether their activities affect the EU market in ways that trigger AI Act obligations. This assessment becomes particularly complex for digital AI services that can be accessed globally or AI systems whose outputs are used across multiple jurisdictions.

Provider status determination directly affects compliance obligations and associated costs, legal liability exposure, market access requirements in the EU, and operational requirements and processes.

Organisations that qualify as providers must allocate significant resources to compliance activities, including legal analysis, technical implementation, documentation systems, and ongoing monitoring and reporting.

Understanding these implications enables organisations to make informed decisions about their AI activities and ensure appropriate compliance measures are in place before AI Act enforcement begins.

The substantial penalties for non-compliance, combined with the complexity of the regulatory requirements, make accurate provider status determination a critical business priority for any organisation involved in AI development or deployment.

Practical Steps for Potential Providers

Organisations that may qualify as providers should begin with comprehensive status assessment activities. This involves reviewing all AI-related activities across the organisation, from research and development through deployment and maintenance.

Here’s a good start. Go to eyreACT platform and perform the self-assessment that will accurately determine not just your system status but also your role according to AI Act:

The assessment will analyse development and deployment arrangements, including partnerships, outsourcing relationships, and third-party integrations that might create provider obligations.

How to Analyse Third-Party Relationships Between Providers, Vendors and Contractors

Third-party relationships require particular attention, as modern AI development often involves complex supplier and partner networks. Organisations must evaluate whether their relationships with AI model providers, development contractors, or integration partners create provider obligations under the downstream provider definition or other provider categories.

Market positioning analysis helps organisations understand how their AI activities are perceived externally and whether they meet the market placement or service provision thresholds that trigger provider status. This analysis should consider both direct commercial activities and indirect market impacts that might fall within the Act’s scope.

Next Steps: Map Your Risks and Implement Your Workflows

Once provider status is determined, organisations must map their specific compliance requirements based on their AI systems’ risk categories and intended uses.

High-risk AI systems carry the most extensive obligations, while other AI systems may face more limited requirements. Understanding these distinctions enables appropriate resource allocation and compliance planning.

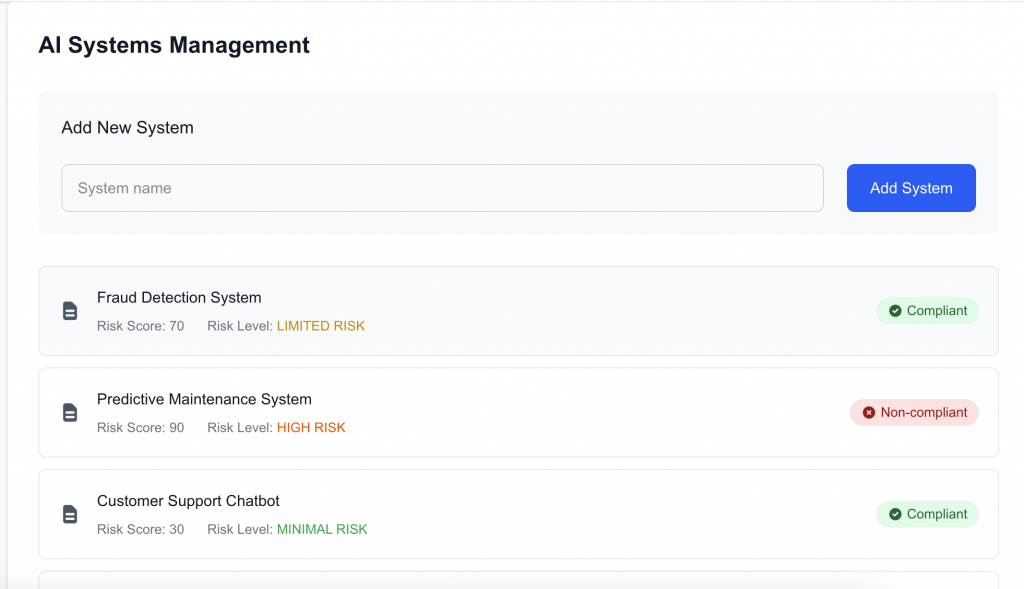

eyreACT does it all automatically for you – you can see all your systems at a glance:

Resource requirement assessment helps organisations understand the human, technical, and financial resources needed for compliance. This includes legal expertise for regulatory interpretation, technical capabilities for risk management and documentation, and operational resources for ongoing monitoring and reporting activities.

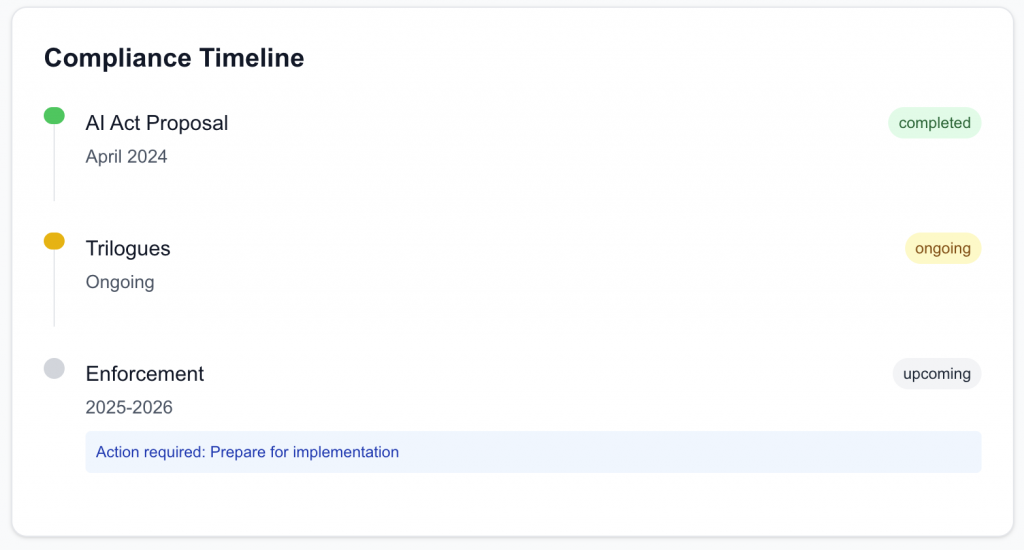

Implementation timeline planning ensures that organisations can meet AI Act deadlines while maintaining their business operations. The Act’s phased implementation approach provides different timelines for different requirements, but organizations need comprehensive planning to address all applicable obligations within the required timeframes.

Luckily, eyreACT makes your timelines and deadlines visible instantly:

Final Thoughts

The definition of “provider” under the EU AI Act represents a cornerstone of the regulation’s approach to AI governance. By casting a broad net that captures various forms of AI development, deployment, and market participation, the Act ensures comprehensive coverage of entities that have meaningful influence over AI systems affecting EU markets and citizens.

The provider definition’s sophistication reflects the complex realities of modern AI development, where traditional notions of software development and distribution have evolved into intricate ecosystems involving multiple stakeholders, diverse business models, and global supply chains. The Act’s approach recognizes that responsibility for AI systems must align with control and influence rather than simple technical development roles.

Turn AI Act compliance from a challenge into advantage

eyreACT is building the definitive EU AI Act compliance platform, designed by regulatory experts who understand the nuances of Articles 3, 6, and beyond. From automated AI system classification to ongoing risk monitoring, we’re creating the tools you need to confidently deploy AI within the regulatory framework.

For organisations operating in the global AI ecosystem, understanding provider status is not merely a compliance exercise but a fundamental business consideration that affects market access, operational requirements, legal liabilities, and competitive positioning. Organisations that understand and effectively navigate provider obligations will be better positioned to compete in the regulated AI landscape that the Act creates.

As the AI Act’s implementation progresses, the provider definition will serve as a critical reference point for determining regulatory obligations across the rapidly evolving AI ecosystem. The definition’s comprehensive approach ensures that the regulation can adapt to technological developments and business model innovations while maintaining clear accountability standards for AI systems that affect European markets and citizens.

This guide is based on the official text of Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 (the AI Act) as published in the Official Journal of the European Union. Organizations should consult with legal counsel for specific compliance advice.